Book Review

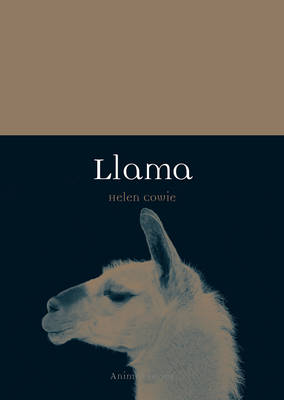

Helen Cowie, Llama (London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2017), 200pp. Paperback ISBN: 9781780237381, 107 illustrations, 67 in colour, £12.95

Readers of Llama Link will no doubt have been intrigued by Helen Cowie’s short article taken from The Indpendent newspaper and published in the last edition (Winter 2018). This covered just a small aspect of Helen’s detailed history of camelids published in book form by Reakin Books in July 2017.

In her Introduction, the author (a senior lecturer in history at the University of York), writes that its purpose was to tell the wondrous stories of llamas, tracing their history from early domestication in South America 7,000 years ago to the 21st century. The Introduction is followed by chapters with the following titles: Alpacas Unpacked, Peruvian Sheep, Enlightened Llamas, From the Andes to Outback, A Very Modern Llama followed by a Timeline and Bibliography.

In the early Inca civilisation, llamas were used to provide food, leather and fleece for clothing, fat to mummify their dead, sacrifices as part of religious rituals and transportation. Even their stomach and kidney stones were valued as lucky charms to provide protection and bring good fortune.

The numbers sacrificed were substantial, as many as 200,000 killed in a year to honour the Sun, but the use of only males and different types/colours used in different months ensured their numbers and diversity were healthy and sustained.

At the time of the Spanish Conquest, llama were put to work in the mining industry, slaughtered on a massive scale to feed the troops and much of their natural habitat was destroyed significantly reducing their numbers and threatening their very survival.

The Spanish made failed attempts to naturalise them back home with the first reported imports in 1578.

Llamas made their first appearance in the UK in the early 1800s, the first reported sighting being in an exhibition at Brooke’s Menagerie in 1805 as mentioned in the previous article in Llama Link.

Alpaca wool became recognised as a valuable commodity in the production of fine garments by Bradford industrialist Sir Titus Salt. Imported into the UK, first as ballast for ships returning from South America, technology was invented by Yorkshireman Benjamin Outram to process the alpaca wool and made Titus Salt a very wealthy man who ploughed much of it back into creating his model town of Saltaire with housing, recreational facilities, hospital and schools for his workers. These, together with his gigantic mill still exists today and despite my Yorkshire prejudices can strongly recommend as worth a visit. Here you will find the iconic statue of an alpaca and representations in the freezes of some buildings (as well as the biggest collection of David Hockney painting etc.). The vast majority of wool came through the port of Liverpool since it was and remains to this date, the primary UK port for South American trade.

It was not surprising given the impacts of the Spanish Conquest on South American camelids and the fact that demand for their wool was outstripping supply, there were attempts to naturalise alpacas in the UK to ensure sufficient and continuous supply of wool. Live animals started to be imported and terrains identified as most suited and under developed in terms of productivity for their early settlement. These included the Scottish Highlands, the Shetlands, mountainous regions of Wales, the Cheviot Hills, and Dartmoor. Some wealthy individuals also saw them as a potential opportunity for money making and/or entertainment. The Earl of Derby, for example bought a herd for his estate in Merseyside (today home of Knowsley Safari Park) and Prince Albert acquired a herd for the Royal Estate at Windsor. Sadly, many died during transit and relatively few of those who survived the journey lived very long after. The problem was little was known about them, their new habitats were different from what they had been used to and their resistances low to common diseases of the new world. Those exported to other parts of the British Empire, the antipodes in particular, had more but still modest success.

Matters improved over time as knowledge increased and the word was spread. Liverpool scientist Alfred Higginson was the first to professionally dissect alpacas from which considerable understanding of their makeup, metabolism and needs were achieved. Discussion and debate between scientists and the farming community ensued in the Liverpool Mercury. Better informed naturalists started to travel further afield and spread the word to shepherds in far flung parts of the British Empire. Another Liverpool naturalist Thomas Atkins wrote technical guidance notes on the welfare of live animals during transportation. Increased interest in these animals led to diversity in objectives for these animals and selective breeding to meet these needs. A certain amount of cross breeding between alpacas, guanacos, llamas and vicunas took place to achieve better meat production, fleece quality, etc. with different emphasises on specific traits in different parts of the world.

Fierce competition from outside the British Empire for British goods started to take its toll on the British textile industry and with it the interest in camelids on a large scale.

Back in their native South America some camelids were threatened with survival and some of their best animals had been exported. This led most South American countries to take protectionist measures including the ban of live exports. As the value of camelids to the economy increased greater recognition was expressed through symbolism with llamas featuring prominently in national iconography such as crests and flags.

The 21st century, as most readers of Llama Link will already know, llamas have become popular animals amongst hobby farmers, used for guarding other animals such as chickens and sheep from predators, carting, trekking, therapy and even golf caddying. At the same time, alpacas have become successful commercial flocks for some large scale farmers. They have inspired artistic and literary representations featured in poetry, novels, children’s films and stories, songs, advertisements.

This book is a must read for all llama enthusiast because it explains their interesting history and how we have arrived at where we are with them today. It is the story of an animal species that once existed in perfect harmony with its human partners, became over exploited, almost to the point of extinction but fought back to show in the modern era its vast potential and adaptability for a wider range of purposes and roles.

Today, in my opinion, it is experiencing something of a renaissance as more specialised hybrids have evolved to be even better suited to purpose be that as pets, productive or working animals. Especially memorable bits for me as a llama keeper and trainer were that even in the old world, there were occasions when the working llama just decided it had had enough and stubbornly stopped in its tracks refusing to go any further. It is comforting to know mine are not alone! Also, that with typically British arrogance, there were commentators in the UK in the early 19th century who suggested that informed with their superior knowledge and husbandry skills they could improve the breed far beyond what the South Americans had achieved, only to fall flat on their faces. However, as I have written in my own book (currently in draft), the North Americans have managed this and is something I am personally committed to working towards in the UK in the 21st century.

I remain unclear why the title is just Llama, although I assume it was to fit into the Reaktion Animal Series of which it is a part. It is just as much about alpacas as llamas and also contains much on guanacos and vicunas. It also provides no clues as to its contents, basically a social and economic history of camelids with some cultural history and anthropology thrown in. For the uninitiated, it does include insights into the behavioural traits of camelids and husbandry requirements and practices. This makes it of wider interest than perhaps this review might suggest, however, since I am addressing the already converted enthusiasts in Llama Link I have not touched upon these aspects.

Dr Richard Cox Hillview Llamas